Howie Burditt, our all-weather china

(china: old southern Africa lingo from London Cockney rhyming slang ‘china plate’ or mate.)

Obituary-Howard Burditt, long-serving Reuters photographer in Zimbabwe

Veteran Reuters Zimbabwean photographer Howard Burditt died in his sleep from heart failure on June 4 in Cape Town. He was 67.

Veteran Reuters Zimbabwean photographer Howard Burditt died in his sleep from heart failure on June 4 in Cape Town. He was 67.Burditt had suffered from poor health including fluctuating blood pressure, his family said.

For many years he covered Zimbabwe’s tumultuous history after independence from Britain in 1980.

During violent elections in 2008 he was arrested for using an unregistered satellite telephone to transmit photographs to Reuters during a clampdown against the press ordered by then President Robert Mugabe. Burditt was detained for three days in a provincial jail notorious for its harsh and filthy conditions in the town of Bindura.

Appearing in court, he pleaded guilty to unknowingly using a phone that had not been licensed under the draconian Broadcasting Services Act and was sentenced to two months imprisonment on the condition of ‘good behaviour’ over the following five years. The sentence was rescinded after a fine of ZW$ 20 billion was imposed, equivalent in the beleaguered, inflationary economy of the day to about US$ 30.

Appearing in court, he pleaded guilty to unknowingly using a phone that had not been licensed under the draconian Broadcasting Services Act and was sentenced to two months imprisonment on the condition of ‘good behaviour’ over the following five years. The sentence was rescinded after a fine of ZW$ 20 billion was imposed, equivalent in the beleaguered, inflationary economy of the day to about US$ 30.

Burditt went on to cover events around southern Africa, contributing to the region’s photographic history. He later stepped back from his cameras and began renovating historic homes and buildings.

He leaves his wife Vanessa and their adult sons Sam and Jake.

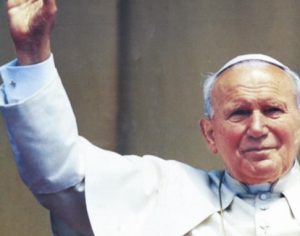

An unexpected meeting with Pope John Paul

I remember Howard as an always smiling and friendly colleague, despite the many stresses of working in Zimbabwe -which included being thrown in a filthy jail for three days in 2008. I first met him long before that in 1988, when I came from Rome to cover an eventful tour of southern Africa by Pope John Paul II.

During the Mozambique leg of the journey, we flew up to Beira in the centre of the country, where the pope celebrated a mass. On the return to Maputo the papal plane landed earlier than expected and well ahead of the following press plane. Local officials seemed caught off guard and Howard, who had stayed in the capital to photograph the pope’s return, found himself standing uneasily at the end of a red carpet alone as the pontiff descended the steps.

Apparently thinking he must be a welcoming local official, the pope marched up to a discomfited Howard and shook him by the hand. Thrown completely off guard, Howard mumbled “How’s it going Holy Father?” before the papal delegation swept off, somewhat puzzled at their unorthodox reception.

Apparently thinking he must be a welcoming local official, the pope marched up to a discomfited Howard and shook him by the hand. Thrown completely off guard, Howard mumbled “How’s it going Holy Father?” before the papal delegation swept off, somewhat puzzled at their unorthodox reception.

Knowing when to back down

I felt we needed to cut down on gunmen, and since several of us were leaving on a reporting trip to the interior, Howard offered to sort it out while we were gone. “Leave it with me,” he said. “I’m an African and I know how to handle these things.”

I felt we needed to cut down on gunmen, and since several of us were leaving on a reporting trip to the interior, Howard offered to sort it out while we were gone. “Leave it with me,” he said. “I’m an African and I know how to handle these things.”Multi-award winning photographer Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi writes:

When I was starting out as a photographer in Zimbabwe, Howard was one of the first people I moved around with. He generously taught me the ropes – especially how to shoot cricket. I’ll never forget being thrown into the deep end by AP to cover one of my first international matches: Zimbabwe vs England at Harare Sports Club in 2003. There I was, clueless, and there was Howard, guiding me around the field, showing me where to stand, what to look for, and when to click. “You should bring a sun hat, Tsvangirayi,” he’d say, grinning, “and don’t forget the sun tan lotion!”

For years, we rolled across Zimbabwe in his car, chasing stories—most of them violent, some unforgettable. I once got kicked in the backside for bringing a white photographer to a farm invasion. At the time, war vets were aggressive, and simply being seen with a white person could get you labeled a sellout. Still, I stuck with Howard, and he stuck with me. He understood the terrain and when I said, not today, he never argued.

Ironically, being black gave me access in ways he couldn’t, and sometimes I got the scoop. But with Howard, skin colour didn’t matter. He was Zimbabwean after all—and to me, always just Howie.

He mastered the art of quick, quiet, precise photography. We were like bank robbers -slipping in and out of chaos with cameras, not guns – and always emerging with visual gold. People feared cameras more than weapons in those days.

We never covered protests alone. That was an unspoken rule – especially for white photographers, who would stick out and risk being targeted. That’s a lesson some young photojournalists still need to learn.

“Let’s not compete for information,” he’d say, puffing on a cigarette. “Let’s compete with our cameras on the ground.”

Rest in peace, Howie. You taught me so much, gave so much – and never asked for credit.

(This year Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi is a Journalism Research Fellow at the MIT academy in Massachusetts and is the first Zimbabwean elected to the judging panel of the renowned ‘World Press Photo’ competition.

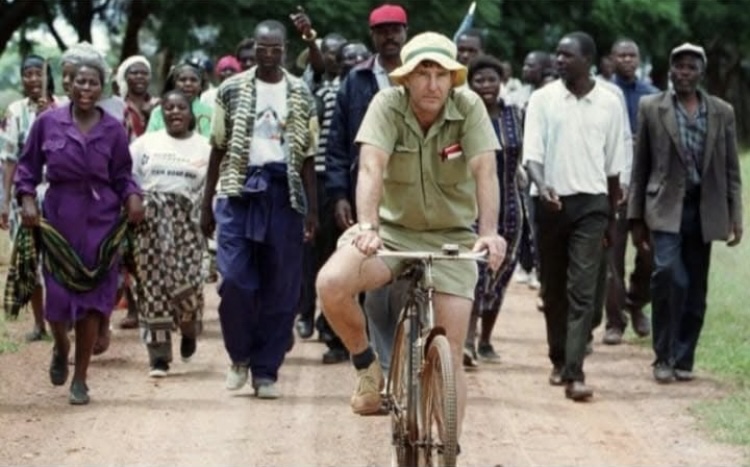

One of Howie’s classic shots during those farm invasions. Farmer Tommy Bailey rides away from his land during the seizures of white-owned farms that began in 2000.

In our younger days, Howie and I became ‘stone chinas’ ( – as firm as granite.) Although we signed up to different news organisations – his British and mine American – it was a time of working hard on the front line of conflict zones and playing hard afterwards – well before cyber journalism, the social media, click bait and ‘fake news’ took over

I did jail time too for the crime of journalism. Was it all worth it? Did we make a difference? Without us throwing light on the violence and political transgressions things would probably have been worse, or so the argument goes.

Happy times

Howie and I were always amused, especially after his satphone arrest, that Baron von Reuter started in the  news business using carrier pigeons in 1850, and that it took three months for handwritten dispatches on the blood-letting in the Crimean war (1853-1856) to reach London by steamship. The first ‘modern’ artillery war was far too noisy for the Baron’s pigeons.

news business using carrier pigeons in 1850, and that it took three months for handwritten dispatches on the blood-letting in the Crimean war (1853-1856) to reach London by steamship. The first ‘modern’ artillery war was far too noisy for the Baron’s pigeons.

Howie will be looking down on us with a furrowed brow as today’s agonies of war rage on.

Oh, Goose!

How your words bring Howie to light again. You couldn’t have written better! Bloody brilliant, old chap!! 👏 🥺😏🥰